Pakistan’s engagement in Central Asia: foreign policy priorities, challenges, and strategic outlook

Pakistan’s foreign policy continues to evolve in response to shifting regional dynamics, global realignments, and domestic imperatives. A critical dimension of Islamabad’s external engagement is its growing focus on the Central Asian Republics (CARs)—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan—whose geopolitical, economic, and strategic relevance has increased markedly since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Pakistan views this energy-rich, landlocked region as both a partner and a gateway to greater connectivity and influence across Eurasia.

Geostrategic Significance of Central Asia for Pakistan

Several factors highlight Pakistan’s interest in Central Asia: geographic proximity, historical and cultural linkages, and the region’s untapped economic potential. Pakistan aspires to serve as a transit corridor for energy and trade between Central Asia, South Asia, and beyond. Historically, the subcontinent has shared deep-rooted cultural, commercial, and political ties with Central Asia, dating back to the Timurid and Mughal eras. India's first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, once noted the cultural resemblance between Pakistan’s northwestern frontier and Central Asia—an observation still relevant today.

Islamabad’s strategic calculus also involves strengthening bonds with the broader Muslim world, in which Central Asia holds a unique place. These nations, despite their Soviet legacy and secular governance structures, remain culturally and religiously significant partners for Pakistan.

Energy and Trade: The Cornerstones of Engagement

One of the most prominent initiatives linking Pakistan and Central Asia is the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline—a project designed to supply Turkmen gas to South Asian markets. However, recurring instability in Afghanistan and strained Pakistan-Afghanistan relations have hindered the pipeline’s progress, underscoring the volatile regional environment that complicates strategic projects.

Pakistan has lobbied for alternative pipeline routes and continues to view energy cooperation as a linchpin of its relationship with Central Asia. Growing energy demand in both Pakistan and India adds urgency to these efforts.

Pakistan’s Export Capacity and Economic Limitations

While Pakistan continues to prioritize economic diplomacy with Central Asia, there are significant limitations to its export capacity. In terms of raw materials and finished goods, Pakistan struggles to offer the range of products needed to meet the diverse needs of Central Asian economies. As a developing economy, Pakistan's primary exports to Central Asia include textiles, sports goods, surgical instruments, rice, and some agricultural products. However, these exports are limited compared to the more diversified industrial and agricultural output of other regional players such as China and Russia.

The lack of a strong industrial base and technological advancements constrains Pakistan’s ability to fully capitalize on the export opportunities Central Asia presents. In particular, Pakistan’s manufacturing and value-added exports remain relatively small, affecting its ability to diversify into more lucrative sectors like machinery, electronics, and high-tech industries, which are crucial for sustained economic engagement.

Trade Diversification and Economic Cooperation

Despite these constraints, there are emerging areas of economic cooperation between Pakistan and the Central Asian states. Key sectors where collaboration is growing include:

1. Energy Cooperation: Energy remains a central pillar of Pakistan’s relations with Central Asia. The TAPI pipeline, despite challenges, is a vital project designed to meet South Asia’s growing energy demands. Additionally, Central Asia’s surplus energy production is crucial for Pakistan, which is looking for diversified energy sources to meet its needs.

2. Transportation and Infrastructure: Pakistan and Central Asian countries have invested in improving regional connectivity. Projects such as the extension of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway to Pakistan aim to enhance trade routes, facilitate the overland transit of goods, and link Central Asia with international maritime trade routes. Pakistan’s Gwadar Port plays a central role in these discussions, providing a vital link for landlocked Central Asian nations to global markets.

3. Agriculture: Agriculture-based cooperation is another avenue where both sides are looking to increase collaboration. Central Asia’s agricultural production, particularly in cotton, fruits, and vegetables, aligns with Pakistan’s needs for such goods, while Pakistan can offer agricultural technology and expertise to enhance production in Central Asia.

While the current trade volume remains limited—often constrained by regional security challenges and infrastructure gaps—there is a growing realization that closer economic ties can be mutually beneficial. Increased cooperation in sectors like mining, textiles, energy, and logistics can help bridge the gap between Pakistan’s limited export base and the broader market needs of Central Asia.

Centralized Foreign Policy and Military Influence

Pakistan’s foreign policy is deeply centralized and heavily influenced by the military establishment. The Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and Pakistan Army play pivotal roles in shaping external relations, often driven by security considerations, religious legitimacy, and geopolitical competition—particularly with India. As scholars have noted, religion significantly informs military strategic thinking in Pakistan, which adds a unique ideological layer to its foreign policy.

In Central Asia, however, Islamabad must balance ideological solidarity with pragmatic economic diplomacy. Despite shared Islamic heritage, CARs maintain secular governance and pursue multi-vector foreign policies, engaging the West, China, Russia, and regional partners alike. Thus, Pakistan cannot rely solely on religious affinity; it must foster practical, mutually beneficial economic and infrastructural cooperation.

Pakistan’s Regional Aspirations and Economic Diplomacy

Islamabad's strategic aims in Central Asia are shaped by five core objectives:

1. Enhancing regional connectivity and trade;

2. Securing energy supplies;

3. Counterbalancing India’s growing presence;

4. Expanding influence in Afghanistan and beyond;

5. Positioning itself as a gateway between Central and South Asia.

Former Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif’s administration has adopted a multidimensional foreign policy approach, prioritizing economic diplomacy as a vehicle for national recovery and regional relevance. Islamabad seeks deeper trade ties and logistical linkages with CARs through initiatives such as the Quadrilateral Agreement on Traffic in Transit (QTTA) and the Transport International Routier (TIR) system.

Bilateral Engagements: Case Studies

Pakistan–Kazakhstan Relations

Kazakhstan, as Central Asia’s largest economy and investment hub, plays a vital role in Pakistan’s regional policy. The countries have strengthened ties through a series of agreements covering trade, cultural exchange, and transport. Kazakhstan’s exports—coal, metals, and fertilizers—complement Pakistan’s growing energy and industrial demands, while Pakistani goods like textiles, pharmaceuticals, and surgical instruments find a market in Kazakhstan.

Trade volume currently stands at $138 million, but both sides aim to raise this figure to $1 billion. Gwadar Port’s connectivity is central to this vision, positioning Pakistan as Kazakhstan’s access point to Middle Eastern and African markets.

Pakistan–Kyrgyzstan Trade and Transit Cooperation

The collaboration with Kyrgyzstan exemplifies Pakistan’s push for regional integration through land-based trade. The National Logistics Corporation (NLC) recently completed its first TIR shipment to Bishkek, signaling a breakthrough in overland trade connectivity. Discussions on extending the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway to Pakistan could provide Kyrgyzstan with much-needed sea access via Pakistani ports.

The establishment of a Kyrgyz Trade House in Lahore further signals commitment to expanding bilateral trade. According to Ambassador Sardar Azhar Tariq Khan, such initiatives are critical for regional integration and economic diversification.

Preferential Trade with Uzbekistan

Pakistan and Uzbekistan signed a Preferential Trade Agreement in 2022, leading to a 40% increase in trade. The countries are now exploring a full Free Trade Agreement (FTA), which could further solidify economic ties. Both governments recognize the strategic importance of deeper engagement, particularly in logistics and transport connectivity.

Geopolitical Constraints and Competition

Despite progress, Pakistan’s efforts in Central Asia are constrained by several factors:

- Geographic barriers, particularly the rugged Afghan terrain;

- Security volatility, especially post-Taliban Afghanistan;

- Regional competition, with China, Russia, Turkey, and Iran offering alternative connectivity and trade routes;

- India’s increasing influence, as New Delhi also seeks energy and trade partnerships in Central Asia.

Islamabad’s framing of itself as the “gateway to Central Asia” must now be recalibrated in light of these realities. Cooperation with other stakeholders—rather than competition—may yield better results for Pakistan.

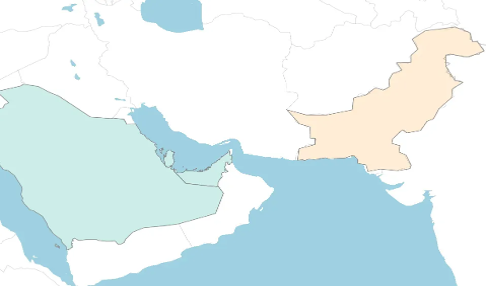

The Gulf Factor: GCC Investments and Strategic Convergence

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states—particularly Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and Bahrain—are investing heavily in Pakistan as a strategic gateway to resource-rich Central Asia. This approach reflects a broader ambition to diversify economic partnerships, secure access to vital natural resources, and expand trade corridors beyond traditional markets. Key initiatives, such as port development and the envisioned Trans-Afghan railway, align with Gulf interests in deepening regional connectivity and gaining strategic depth.

Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, in particular, are seeking to strengthen geographical connectivity through infrastructure projects that facilitate Central Asian access to Pakistan’s transport and logistics networks, including its ports on the Arabian Sea. For instance, the Trans-Afghan railway would allow Uzbekistan direct linkage to Pakistan, creating a seamless corridor from Central Asia to the Gulf.

At the same time, Pakistan has actively welcomed Gulf investment and financial aid as it grapples with an ongoing economic crisis. In July, Saudi Arabia extended $2 billion in aid to Islamabad—a gesture described by Pakistani officials as a “great gesture” reflecting deepening ties. These investments not only offer Pakistan immediate financial relief but also enhance the soft power and long-term economic footprint of the Gulf states in South Asia.

Strategic Implications: A Triangular Network Emerges

The increasing alignment among Pakistan, Central Asia, and the Gulf suggests the emergence of a triangular network grounded in shared interests—namely, trade, energy security, and regional integration. For the GCC, investing in Pakistan offers both economic returns and strategic influence, while Central Asian nations gain crucial access to global markets via Pakistani ports.

However, this growing Gulf footprint introduces new dynamics in Pakistan’s foreign relations—potentially recalibrating its longstanding reliance on China. While China’s $62 billion CPEC investment under the Belt and Road Initiative remains dominant in scale and scope, Gulf-backed projects could challenge Beijing’s primacy in the short term, particularly in sectors like energy, logistics, and mineral exploration.

Conclusion: A New Frontier for Pakistan’s Foreign Policy

Pakistan’s evolving engagement with the GCC and Central Asia represents a pragmatic shift toward economic diplomacy, infrastructure development, and multilateralism. While historic ties and ideological affinities lay the groundwork, future cooperation will be defined by trade, transport, and energy connectivity.

To fully capitalize on this momentum, Pakistan must address critical domestic challenges, including political instability, security threats, and competing regional interests. By adopting a balanced approach that leverages partnerships with both China and the Gulf, Pakistan can position itself as a central node in a new Eurasian economic and strategic corridor, reshaping its role in the regional order.