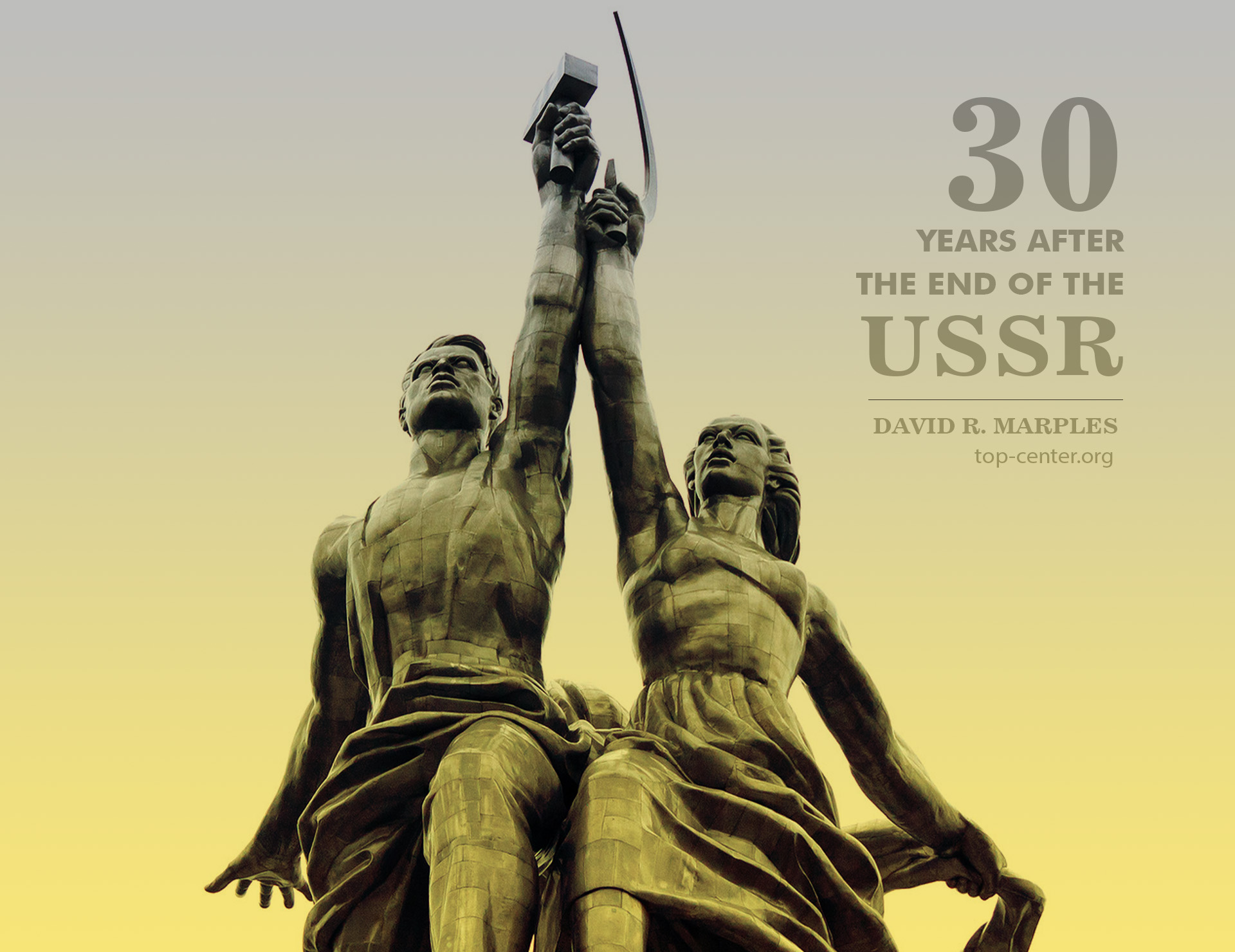

Thirty years after the end of the USSR

December 31 marks three decades since the end of the Soviet Union (USSR). What were this Super Power's achievements, why did it disappear from the map of the world, and what is its legacy today in Russia?

Stalin Triumphant

In February 1945, Iosif Stalin and the leaders of the United States (Franklin D. Roosevelt) and Great Britain (Winston Churchill) met in the Crimean resort town of Yalta to discuss the future of the war, the fate of Hitler's Germany, and the division of Europe. The occasion marked an epoch: a Soviet leader was not only on the same platform as the two main imperialist powers, but firmly in control of the discussion. His armies had already inflicted devastating blows on the Germans and their Allies in battles at Stalingrad and Kursk, and had destroyed German Army Group Centre in the Battle of Bagration.

Victory in the 'Great Patriotic War', as the Soviet leaders termed the Second World War, legitimized the Soviet Union, the world's first Communist state, founded in November 1917 when Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky led a Bolshevik uprising in Petrograd (St. Petersburg). By 1922, following a bitter civil war from which the Bolsheviks emerged victorious, several states joined together to form a Union (Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Transcaucasia). By the 1930s, Kazakhstan and the Central Asian States had been added, each with their own Soviet republic.

In 1939, following a non-aggression Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, eastern Poland was attacked by the Red Army, occupied, and its territories added to those of the Ukrainian and Belarusian republics. In 1940, the three Baltic States were added too, and Moldova was given republican status. Altogether, there were now fifteen Union republics. Transcaucasia had been divided into three republics based on its ethnic populations: Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis.

The Cold War

From this apex in 1945, the Soviet Union entered an ideological Cold War with the United States and much of the Western Allies as the coalition against Hitler collapsed. The two leading postwar powers embarked on a dangerous arms race that included both atomic and conventional weapons.

By 1949, Germany was firmly divided into two: the Federal Republic of Germany with its capital on Bonn, and the smaller German Democratic Republic, with its capital in East Berlin arose from the Allied occupation zones. The Western powers formed a defensive military alliance: the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in this same year that was clearly directed at the Soviet Union.From 1961, the East Germans constructed a wall through Hitler's former capital, to prevent an outflow of population to the west.

Six years later, the Soviet Union and its East European Allies formed a counter-organization called the Warsaw Pact, based on a renewable contract initially lasting ten years. The following year, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced the crimes of his predecessor Stalin, particularly the Purges of 1937-38 in which old Bolsheviks had been targeted along with thousands of others. According to Khrushchev, the Soviet Union had deviated from the path of Lenin. The speech, at the 20th Party Congress, prompted demonstrations and riots in Poland and Hungary. Though a compromise was reached whereby Poland could seek its own path to socialism, the Soviet Army invaded Hungary to prevent its leaving the Pact.

Khrushchev's Reforms

Khrushchev attempted to reform Soviet agriculture, but his programs were erratic. He tried to cultivate Virgin Lands, match the United States in dairy production, and grow corn in the black earth of Ukraine. By 1961, the Soviet Union became a grain importer, an embarassing situation that resulted from a series of failures on collective and state farms. He did have one lasting achievement, though one far beyond his own level of competence: the Soviets launched the first space capsule Sputnik in 1957, and the first human in space--Yury Gagarin in 1961. Their lead in the space race lasted eight years until the Americans landed a man on the moon.

Khrushchev's ebullience led to several rash boasts about overtaking the United States, and in the military sphere, his most questionable manoeuvre was to install nuclear weapons on the island of Cuba, capable of reaching most of the United States. The Americans, led by President John F. Kennedy, imposed a quarantine. It was the closest the world had come to a nuclear confrontation, but Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles with the condition that Communist leader Fidel Castro would be left in power. The failure over Cuba combined with agricultural disasters saw Khrushchev replaced by Leonid Brezhnev in an internal KGB coup in 1964.

Brezhnev: the time of "stagnation"

By 1975, on paper, the Soviet Union had reached the peak of its powers with Brezhnev in the position of General Secretary. It had attained military parity with the United States. The Communist system, however, had decayed. Its ageing leaders indulged in ritualistic self-praise and a cult of the leader. But whereas such a cult had worked with Stalin, Brezhnev lacked both the charisma and intelligence to generate mass adulation. He had several strokes from the mid-70s onward, and his speech became slurred through a combination of drugs and sleeping pills.

The Soviet Union was now a bitter enemy of China, with several border clashes. On a global level, the two Communist powers competed for the support of decolonized states as the former Western empires receded. At home, the economy slowed down rapidly. Abroad, the technological advancements of the Americans, particularly in the military sphere, left the Soviets behind. By the early 1980s, US president Ronald Reagan was touting a Strategic Defense Initiative (known colloquially as Star Wars), the notion of a shield to protect the American homeland from nuclear missiles. It was far-fetched, but the Soviets were incapable of a response.

The Reasons for the Collapse of the USSR

In March 1985, after a succession of deaths among the leadership, Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. He was a younger, more personable and modern leader who recognized the problems plaguing Soviet society. Above all, he recognized the inertia at the higher levels of the party and sought to return Soviet society to the ideals envisaged by Lenin. Six years and nine months later, he resigned his office and the Soviet flag descended on the Kremlin. The question is why?

Though the reasons for such a collapse have no simple answer, we can pose some suggestions.

First, the arms race was a factor in the decline of living standards: the Soviet Union was a Super Power with a third world economy. But it was not the decisive reason for its dissolution. By the late 1980s, the United States regarded Gorbachev as the ideal leader in Moscow, the man who ended the Cold War in eastern Europe, and who had made significant reductions to his nuclear arsenal. Gorbachev by this time was far more popular in Washington, DC than in Moscow. The Americans did not want to see him fail.

Third, Gorbachev had sought to reform the party, but when that seemed impossible to achieve, he sought to override it through creating new institutions: a Congress of People's Deputies, multiparty elections, and, not least, a Soviet presidency led by himself. But, as a leader, Gorbachev lacked the resolve to take decisive measures against the Communist Party and KGB, so that by late 1990 and early 1991, he recalled the so-called hardliners to office. All of them supported the putsch in August 1991 to try to stop Gorbachev's proposed Union Treaty with the republics.

This brings me to the two short-term factors that were probably decisive. The first began with Glasnost, Gorbachev's policy of frankness and self-criticism that began with attacking Stalin in the media, but then metamorphosized into criticisms of other parts of Soviet life: the aftermath of the 1986 nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, centralized decision-making, and the desire of the national republics for more control over their own economies and political life. By 1990, most Soviet republics had declared sovereignty, leaving the Moscow centre with control only over defence and foreign policy.

Such decentralization was not unusual in a federal state but in June 1991, Gorbachev's great rival, Boris Yeltsin, was elected President of Russia, and promptly moved into the Kremlin. The Russian Congress of Deputies rivaled the Soviet one in authority. In 1991, Russia gradually claimed ownership of Soviet resources. After the failed putsch, Yeltsin took over the army and nuclear weapons, and banned the Communist Party. Several republics, including Ukraine and Belarus, declared independence. Gorbachev was essentially deprived of a role, and his defeat was complete once leaders of Ukraine and Belarus, Leonid Kravchuk and Stanislau Shushkevich, supported Yeltsin's initiative at a meeting in the Belavezha Forest on the border with Poland.

In short, the first Communist state, which reached a peak under Stalin, dissolved from within. Today, its achievements, particularly the victory over the Nazis, are hailed by President Putin and other Russian leaders, but they have no wish to restore the Soviet Union. Its innate weaknesses are only too apparent. Instead, the focus is on its achievements, and specifically the war years and Soviet victory. In this way, Stalin has reemerged as a significant figure while the war has attained mythical status and the official narrative can no longer be questioned.

Whatever the logic of such a development, it has created a natural historical progression from the Soviet Union to the Russian Federation. With the exception of Belarus, ruled by the authoritarian Aliaksandr Lukashenka, no other post-Soviet republic has laid claim to the Soviet legacy. Many have rejected it outright. The first Russian president Boris Yeltsin had followed suit, but Putin has made the war and the Soviet victory the central theme of Russian identity building.

By the same token, even though official Russia has revived the memory of the Great Patriotic War, it has ignored Stalin's crimes, the Gulag, KGB attacks on dissidents, and the unsavory Pact with Hitler in August 1939 that led to the destruction of the Polish republic and the annexation of the Baltic States. On the contrary, the message is that the Soviet army, alone, saved Europe from Nazi German conquest and enabled the freedoms available in the EU today. Its commander-in-chief was Stalin. It is not acceptable to dwell on his misdeeds.

These comments were also published in ILNA News.