Recasting multi-vectorism: a western-anchored strategy for Azerbaijan

The rapid erosion of the liberal international order has generated multiple dislocations in the South Caucasus, placing Azerbaijan at the crossroads of competing region-building projects. As the unipolar, neoliberal framework recedes, Azerbaijan’s long-standing multi-vector foreign policy faces mounting challenges under intensifying external pressures.

During the unipolar era, international institutions anchored in liberal norms provided a stabilizing framework that subordinated regional processes to broader systemic imperatives. In the South Caucasus, this produced a relatively stable and predictable environment, effectively freezing many regional conflicts.

Today, these institutions are visibly weakening, their regulatory and discursive authority diminished. Global issues are increasingly addressed outside traditional institutional frameworks. A telling example in the South Caucasus is the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Once a central pillar of cooperative security and conflict mediation, the OSCE’s relevance has eroded. In the post-Soviet space, its Minsk Group—established in the 1990s to mediate the Azerbaijan–Armenia conflict—has been sidelined in recent peace efforts, weakened by divisions among its co-chairs.

Created to facilitate resolution, the Minsk Process now often appears as an obstacle to progress.

In a recent historic meeting in the United States, attended by President Donald Trump, Azerbaijan and Armenia jointly appealed for the closure of the Minsk Process and its related structures—signaling a formal end to hostilities and a shift away from the institutional legacy of the liberal order.

Frontier Dynamics and the Competition for Territorialization

As the unipolar neoliberal order fades, the stable economic, political, and security framework it once offered—both globally and in the South Caucasus—has unraveled. In the limbo between the decline of the old order and the rise of a new one, interconnected frontier and territorializing dynamics begin to take shape.

Frontier dynamics happen when old systems and rules no longer hold, and new ones are not yet fully in place. They break down established patterns of life—such as who owns land, who holds political authority, and what rights and agreements people can depend on. In these moments, borders may shift, power may be contested, and uncertainty grows. While this often causes conflict and instability, it also creates openings for new arrangements to be negotiated and new forms of order to take shape. In short, frontier dynamics describe the messy and uncertain period between the collapse of one system and the construction of another.

Territorialization is the process of building or rebuilding control when the old order has broken down. It happens when new boundaries are drawn, rights are redefined, authority is claimed, and resources are reorganized. Sometimes this is done through physical control—like seizing land or borders—and sometimes through symbolic acts, such as declaring sovereignty or changing legal frameworks. In practice, territorialization is how competing groups or states contest to turn uncertainty into new, more stable forms of order.

The South Caucasus is now one of the important arenas for these contests. Regional and global powers advance competing visions for territorialization, each seeking to shape governance, authority, and control in ways that serve their strategic interests.

Risks to a Multi-Vector Policy in a Frontier Context

The acceleration of frontier dynamics has drawn Azerbaijan deeper into overlapping territorialization projects, increasing the complexity of its regional environment. This shift has heightened the vulnerabilities of its multi-vector foreign policy—a strategy once prized for maximizing autonomy by exploiting the loopholes of the liberal order.

Historically, Azerbaijan’s multi-vectorism thrived in a fluid, contested South Caucasus, allowing Baku to maneuver between rival power centers. In theory, the global trend toward decentralized multilateralism could have enhanced this flexibility. In practice, frontier dynamics have widened the gap between global and regional agendas, shrinking areas of convergence while multiplying competitive arenas.

Where the liberal order fostered cooperation based on absolute gains, its erosion has given rise to relative-gains thinking, mercantilist rivalries, and zero-sum logic—conditions reminiscent of a Hobbesian state of nature. In this environment, Azerbaijan’s balancing capacity is weakening. Divergent commitments now require harder trade-offs, eroding the bargaining leverage once afforded by playing multiple sides.

Regional volatility increases the risk of security spillovers, while economic and infrastructural fragilities undermine the stability of trade corridors and investment flows critical to Azerbaijan’s prosperity. The flexibility that once defined multi-vectorism now amplifies strategic dangers rather than mitigating them.

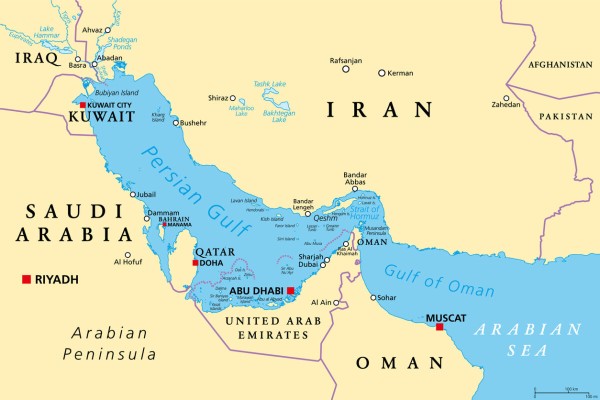

The rapid pace of frontier-driven changes further strains Azerbaijan’s institutional and strategic capacities. Pulled into trans-regional dynamics linking the South Caucasus with Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, Azerbaijan faces both opportunity and exposure to instability across multiple theatres. With fiscal space narrowing and security costs rising, maintaining a balanced multi-vector posture is becoming unsustainable. Without decisive adaptation, Azerbaijan risks being reduced to a buffer zone or a resource corridor—an object of the regional order rather than a shaper of it.

Indeed, the multi-vector policy designed to safeguard autonomy now inadvertently fuels frontier dynamics by engaging multiple, often competing power centers. This overlap of ambitions fosters external influence, strategic incoherence, and deepened vulnerabilities—pushing Azerbaijan toward the danger of becoming either a geopolitical buffer or an extraction hub for foreign powers.

Way Forward: Disabling Frontier Dynamics

The most effective strategy for countering frontier dynamics in the South Caucasus is for Azerbaijan to pursue its own territorialization project through deeper regional integration. Incorporating Armenia into regional transport and energy networks would not only serve Azerbaijan’s strategic interests but also foster a more connected South Caucasus, ease tensions, and potentially orient Yerevan toward the western vector of Azerbaijan’s foreign policy—thus reinforcing regional stability and limiting destructive external interference.

Normalizing relations with Armenia and enhancing ties with Georgia could further close strategic gaps, de-escalate tensions, and constrain foreign manipulation. Recent peace talks, a joint declaration with Armenia, and sustained engagement with Georgia indicate Baku is already advancing along this path.

Yet regional integration alone has clear limitations. Azerbaijan and its neighbors lack the institutional capacity and resources to build a cohesive, self-sustaining regional framework capable of resisting external influence. Deep mistrust, political fragmentation, external manipulations and underdeveloped mechanisms for cooperation remain significant barriers.

Given these constraints, Azerbaijan should also align selectively with external actors whose territorialization aims are compatible with its own and those of regional partners. Here, regional integration and targeted external alignment must be seen as complementary, not competing, strategies.

Strengthening the western vector of Azerbaijan’s multi-vector policy—anchored in strategic convergence with Türkiye—offers the most viable course.

This alignment rests on deep-rooted ties: since the 1990s, Azerbaijan has oriented its major infrastructure, energy, and transport projects toward Turkish and European markets. Türkiye provides critical security guarantees and shares an interest in a stable South Caucasus, which also grants Ankara alternative routes to Central Asia. Recent growth in Azerbaijan–Central Asia cooperation in energy and transport complements Türkiye’s regional ambitions, reinforcing this partnership.

Türkiye’s engagement boosts Azerbaijan’s deterrence and creates favorable conditions for attracting Western investment. However, Türkiye’s capacity as an economic anchor is limited by resource constraints and overextension in multiple conflict zones. To address this, Azerbaijan should work to draw Western economic and strategic interests more directly into the South Caucasus and Central Asia—leveraging Türkiye as a security guarantor and positioning Western partners as principal investors and market integrators.

There is already significant space for convergence between Türkiye, the West, and Azerbaijan, particularly in advancing South Caucasus integration and deepening Central Asia engagement. Historically, the West actively promoted regional integration and sponsored key projects in South Caucasus. Today, the South Caucasus aligns with Western priorities by offering alternative routes to Asia and access to vital hydrocarbons. Since Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, alternative energy routes and greater access to resources from the South Caucasus and Central Asia have become essential for easing pressure on Europe’s energy markets.

Coordinated engagement across these regions could close strategic loopholes, deter destabilizing moves by Iran and Russia, and channel investment into long-term connectivity and infrastructure. Expanding transport and energy corridors into Central Asia would diversify markets, provide alternatives to Chinese-dominated routes, and create new economic opportunities.

With oil revenues declining and geopolitical rents shrinking, Azerbaijan urgently needs to diversify its economy. Coordinated connectivity with Central Asia—underpinned by Türkiye’s security role and Western capital—offers a clear path forward. At present, Ankara, Baku, and Western actors often pursue overlapping goals in parallel or even in competition; aligning these efforts would multiply their impact.

Reinforcing the Western Vector

In today’s volatile geopolitical climate, Azerbaijan’s most realistic path to disabling frontier dynamics lies in reinforcing its Western-oriented multi-vector policy, centered on a strategic partnership with Türkiye. This approach addresses immediate security needs, opens new channels for economic growth, and consolidates Azerbaijan’s role as a pivotal connector in the emerging regional order.

While frontier dynamics present serious risks, they also create opportunities for strategic redefinition. By combining regional integration with targeted external alignment, Azerbaijan can shift from being a reactive buffer state to a proactive regional connector—anchored in coherent partnerships and guided by its own territorialization vision.