Can Pezeshkian’s poetry diplomacy thaw Azerbaijan-Iran tensions?

The echoes of Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian’s historic visit to Baku in April still resonate across the Araz River. Among the many aspects of this visit, what caught the attention of political analysts and region observers alike was Pezeshkian’s unexpected yet symbolic use of “poetry diplomacy.” His recitation of verses from Mahammadhossein Shahriyar’s iconic poem “Heydarbaba’ya Salam” (“Greetings to Heydarbaba”) struck a chord with Azerbaijani audiences, evoking a shared cultural memory that transcends political borders.

This gesture, delivered first during an interview with Azerbaijan Television and again at a joint press conference with President Ilham Aliyev, was received warmly by many north of the Araz. In a region where historical grievances and geopolitical tensions often dominate discourse, such soft power symbolism stood out. Yet, the question remains: Can poetry and cultural overtures help melt the enduring ice in Azerbaijani-Iranian relations?

The cultural signal

“Heydarbaba,” penned by the famed Iranian Azerbaijani poet Shahriyar, is more than just literature. It is a nostalgic ode to the poet’s childhood village and a lament for the fragmentation of identity caused by political borders. For many Azerbaijanis, both in Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan, the poem resonates with a collective longing for unity and cultural affirmation. Pezeshkian’s decision to quote it was therefore no coincidence—it was a calculated signal of shared heritage and goodwill.

This was not the first time Rais Jomhur Pezeshkian used poetry in the political arena. Several months before his visit to Baku, he recited lines from the same poem in Iran, drawing criticism from some hardline officials. The reaction revealed the sensitivity surrounding ethno-cultural expressions in Iran, especially when they touch on Azerbaijani identity. Despite this, Pezeshkian has remained committed to a more inclusive rhetoric, positioning himself as a moderate voice open to reconciliation.

The geopolitical iceberg beneath the surface

While poetic gestures can warm hearts, they do little to address the structural roots of tension between Azerbaijan and Iran. The trajectory of bilateral relations since 2020 has also been volatile with key flashpoints—such as Iran’s large-scale military drills near the Azerbaijani border and the 2023 terrorist attack on Azerbaijan’s embassy in Tehran—having severely undermined trust. While recent months have seen a flurry of diplomatic engagement and economic cooperation agreements, the deep-seated geopolitical and ideological rifts remain largely unresolved.

Several (permanent?) factors continue to complicate the relationship:

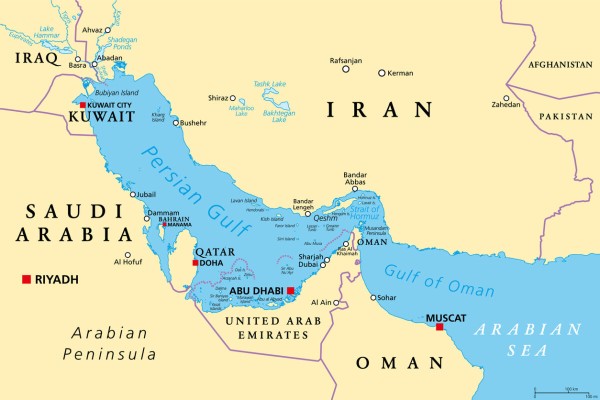

• Geopolitical rivalry: Iran views Azerbaijan’s growing strategic alignment with Israel and Turkey with increasing suspicion. This cooperation—particularly in the defense and intelligence sectors—is perceived by Tehran as a direct challenge to its regional posture. Iran is especially wary of Israel’s presence near its northern borders, viewing it as a security threat with potential implications for internal stability.

• Competing historical narratives and denial of agency: Tehran’s perception of Azerbaijan echoes, in some ways, Moscow’s attitude toward Ukraine—viewing it not as a fully sovereign and distinct nation, but as a territory with historically subordinate status. (Azerbaijan as Iran`s Ukraine?) This perspective manifests in attempts to strip Azerbaijan of an independent cultural, political, and historical identity, framing it instead as part of a Persian or Iranian civilizational sphere. Such narratives diminish Azerbaijan’s agency and fuel nationalist responses in Baku, which also like to remind that it was actually mainly Azerbaijani/Turkic dynasties who ruled over the present-day Iran between the 11th and 20th centuries.

• Cultural and identity politics: Tehran harbors deep-rooted fears of Azerbaijani irredentism, especially given Baku’s cultural outreach to ethnic Azerbaijanis in northern Iran. These concerns are heightened by the promotion of Turkic narratives from both Azerbaijan and Turkey, which Tehran interprets as efforts to undermine its territorial integrity and disrupt internal cohesion. The increasing visibility of Turkic identity across borders intensifies Iran’s sensitivity to ethnic nationalism within its own diverse population.

• Secularism vs. Theocracy: Azerbaijan’s secular, West-facing posture stands in sharp contrast to the Islamic Republic’s ideological foundations. This fundamental dissonance shapes mutual distrust—not only at the level of state elites but also within broader public opinion—creating an additional barrier to sustained political engagement.

In this context, even the seemingly innocuous line recited by Pezeshkian—“Who separated us?”—takes on layered meanings. For some, it is a poetic reflection on shared identity; for others, it may subtly allude to Tehran’s own historical grievance over the 19th-century separation of Northern Azerbaijan from Persia (which was by the way ruled by an Azerbaijani Turkic dynasty, Qajar) under the Treaty of Turkmenchay. Whether intentionally or not, such phrases risk being interpreted in multiple, sometimes conflicting, ways.

A regional pattern of Poetry Diplomacy?

Pezeshkian’s poetic overture recalls a similar moment in December 2020, when Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan recited a poem during a military victory parade in Baku. His reference to the separation of the historical Azerbaijan drew a sharp rebuke from Tehran, which viewed it as a provocation, signaling support for Turkic unity and indirectly challenging Iran’s sovereignty over its Azerbaijani-speaking provinces.

The recurrence of this poem in regional politics points to the growing importance of (Oriental-style) cultural symbolism in the South Caucasus geopolitics. Whether used to foster unity or assert soft power, poetry is no longer just a form of expression—it is becoming a tool of diplomatic messaging, nation-branding, and identity politics.

The limits of verse in an unpoetic world

Despite the warmth generated by Pezeshkian’s poetry, it would be naïve to assume that bilateral relations that are structurally antagonistic can easily be transformed. The Iranian “deep state”—comprising elements of the IRGC and hardline clergy—still wields significant power and remains wary of Azerbaijan’s external alignments. Until this internal power imbalance shifts, even the most heartfelt gestures from the moderate camp will face limitations.

In the end, poetry cannot paper over power. While Pezeshkian’s recitation may have charmed television audiences and softened media headlines, it does not change the brutal arithmetic of geopolitics. Tehran remains fundamentally uneasy about a rising, assertive Azerbaijan that is not only militarily capable but also ideologically alien—secular, nationalist, and allied with Iran’s foremost adversaries. The poetry, in this sense, is less a peace offering than a carefully worded lullaby to distract from sharper instruments at play.

Baku, for its part, does not mistake sentiment for strategy. It should understand full well that behind Pezeshkian’s smile stands a system—anchored in clerical militarism and strategic paranoia—that has not changed its view of Azerbaijan as a disobedient periphery. Recent economic agreements and diplomatic niceties may lubricate bilateral mechanisms, but they do little to build genuine trust in a relationship defined by mutual suspicion and layered grievances.

Moreover, the enduring specter of ethnic nationalism in Iran—or Tehran’s fear of it—continues to be the elephant in the room. Iran’s sprawling, multiethnic structure is vulnerable to the very cultural forces it now tries to co-opt through poetic performance. The regime may tolerate Pezeshkian’s verse, but it will not tolerate a shift in loyalties among its Azerbaijani population. In that sense, the real audience for this diplomacy is not (only) Baku, but Tabriz.

The reality is simple: as long as Tehran’s strategic calculus is shaped by paranoia, and Baku’s by pragmatism, the poetry will remain a decorative flourish—a seasonal gust, not a structural wind. In the unforgiving logic of the region, verses may soothe, but historical and geopolitical realities still speak louder.