Armenia and Azerbaijan peace deal text finalised: what is next?

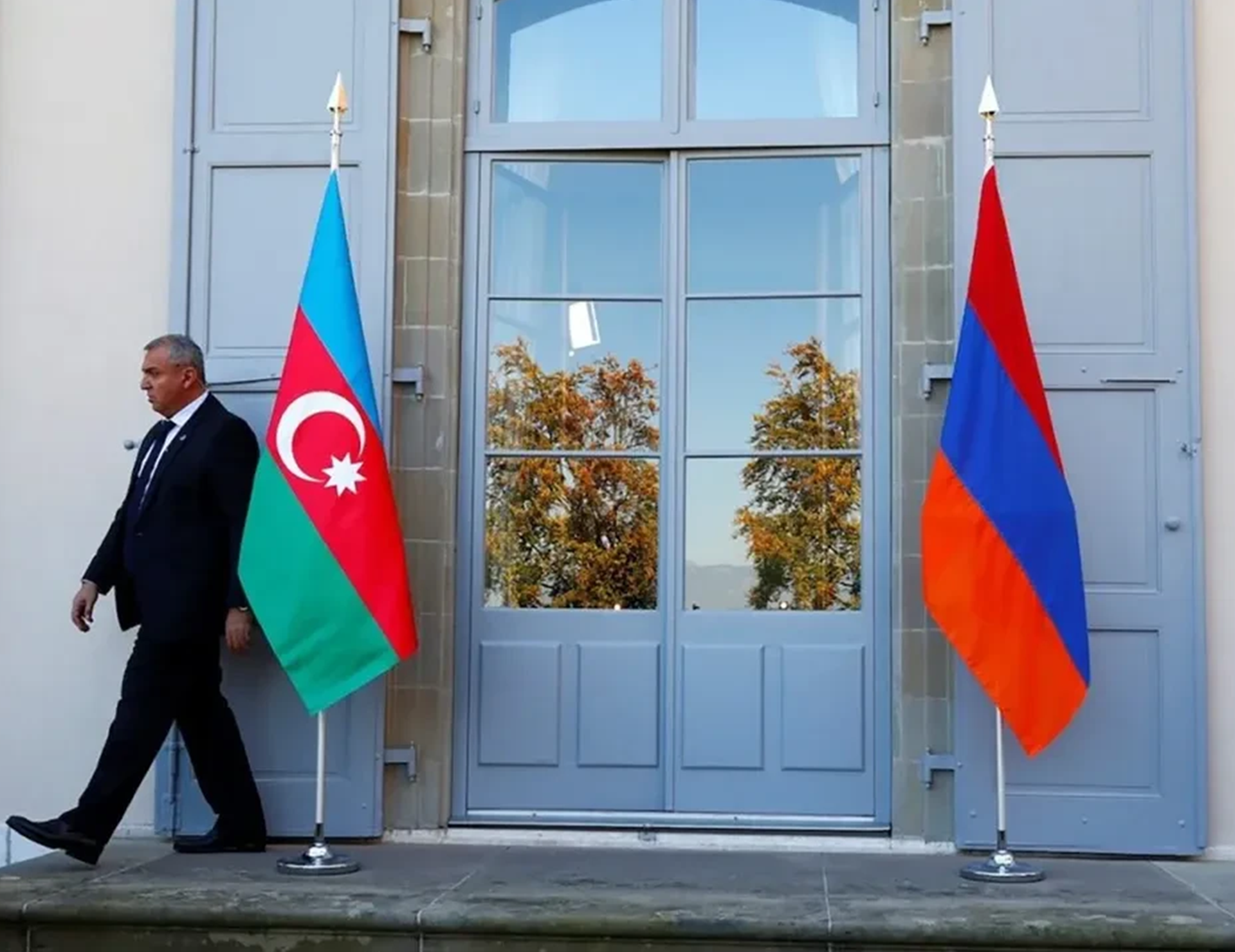

During the annual Global Baku Forum yesterday, Azerbaijan’s Foreign Minister Jeyhun Bayramov made a long-awaited announcement: the text of a peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan has been finalized. Shortly after, the news was also confirmed by Armenia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

This finalized draft is the 12th version of the agreement, following more than 15 rounds of exchanges between the foreign ministries of both countries. The first serious discussions about a comprehensive peace treaty began in late 2021 but remained vague and slow-moving. In March 2022, Azerbaijan proposed a five-point peace plan, and the following month, in a Brussels meeting, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev officially agreed to begin drafting the treaty.

Many had hoped that the peace treaty would be signed during COP29, but those expectations were dashed after Armenia declined to attend the event. Subsequently, attention shifted to the possibility of the treaty being signed by the end of 2024, especially after positive statements emerged in December that the deal was nearly finalized. However, despite the optimism, two out of the 17 articles in the draft peace agreement remained unresolved.

Now, after nearly three years of negotiations, the agreement’s text is complete, and Armenia and Azerbaijan are closer than ever to a peace deal. At the same time, with agreement on these two articles, the signing of the peace treaty can seem within reach, merely a matter of finalizing technical details such as the location and timing. However, while this is indeed a quiet achievement and critical breakthrough in the history of Armenia-Azerbaijan negotiations, there are still unresolved political and legal challenges still looming. Until these remaining disagreements are resolved, it remains uncertain when the treaty will finally be signed.

The key issues involve Armenia’s constitution and the dissolution of the OSCE Minsk Group. Jeyhun Bayramov stated that in the next phase, Armenia must remove any territorial claims against Azerbaijan from its constitution, and the remnants of the Minsk Group should also be dissolved. This reference to a "next phase" suggests a three-phase process, which can be broken down into a 2+2+2 framework.

The first phase of 2 involved resolving two key provisions of the treaty - article on the third-party presence on the border, and article on the annulment of mutual legal claims. With Armenia agreeing to these on March 13, the process now moves into the next stage, which presents new, more politically sensitive challenges.

The second phase of 2 includes amendments to Armenia’s constitution and the dissolution of the OSCE Minsk Group. For Azerbaijan, these are critical preconditions for lasting peace. Baku argues that as long as Armenia’s legal framework includes language that could be interpreted as territorial claims on Azerbaijani territory, there is a high probability for future escalations.

The OSCE Minsk Group is another major sticking point. Azerbaijan argues that the group's mandate became obsolete after the Second Karabakh War in 2020. In Baku’s view, allowing the Minsk Group to remain involved could create space for renewed international debate over Karabakh’s status - a scenario Baku wants to avoid at all costs. While Armenia has agreed to the group’s dissolution in principle, it has continued to engage with its members. In February, Pashinyan stated that the latest peace draft was also submitted to the OSCE Minsk Group for review - a very contradictory action.

And the last pair of items include the opening of the communication lines and the issue of border delimitation. Both sides have agreed in principle to restore transportation and trade routes. However, the specific details, such as the exact routes and security arrangements, are not agreed upon. The details of this stage remain highly sensitive, as both Baku and Yerevan hold deeply entrenched positions. In turn, border delimitation is a process that requires time. If we look at the example of Azerbaijan and Georgia as well as Armenia and Georgia, where some parts of their border remain undelimited even today, we can conclude that this component may take longer to finalize and will likely follow a similarly gradual path.

The 2+2+2 framework does not necessarily imply that a peace deal will be signed only after all these phases are finalized. The announcement about the text and the recent progress in the bilateral track coupled with external factors can accelerate the peace process and yield the signed agreement perhaps even earlier.