How it feels reading policy papers on the EU’s neighborhood: A look from neighborhood

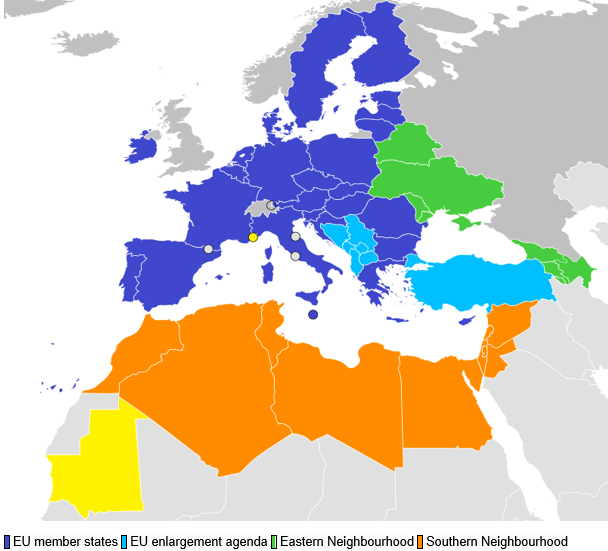

Photo: EU Neighbourhood Countries

The EU’s Global Strategy of 2016, in light of a changing security environment, calls for ‘…a more confident and responsible European Union.’ The strategy envisions a dynamic role for the EU ‘…to the east stretching into Central Asia, and to the south down to Central Africa.’ Looking across the eastern and southern neighborhoods of the EU, it is difficult to claim the EU has been successful in enacting provisions foreseen in the strategy over four years since its announcement. Correspondingly, the number of policy papers for more active EU engagement in the neighborhood has been on the rise recently. Yet sitting in a neighborhood country and reading them does not always make a good impression and sense, as a few perceptions about the neighborhood and, consequently, policy advocacies seem problematic in many aspects. Some miss important points concerning spaces of possibilities in the neighborhood when listing recommendations.

Neighborhood as terra nullius. A group of policy papers ignore the existence of the political communities in the EU's neighborhood. From the viewpoints of such papers, the neighborhood appears as a piece of land under no one’s jurisdiction around Europe. It is a kind of land where the EU has an interest over and consequently the right to interfere and to carry out civilizing mission to facilitate the modernization and the Westernization of indigenous peoples. Other actors also compete for influence and territorialization in this terra nullius. Recently, compared to other powers the EU does not do well. To optimize possible negative internalities and externalities of such tendencies, they suggest, the EU should take countermeasures (as the EU is usually late and not well-positioned) against its rivals. In this particular context, the outlook of political assemblages of the terra nullius and their needs are either absent or less of concern.

Neighborhood as a uniform region. Some comprehend the neighborhood as a single unit having identical features. This view makes uncontextualized, increasingly disconnected from the reality on the ground and one size fits all types of solutions possible in theory, yet in practice unimplementable as the neighborhood is very diverse. Worthwhile to mention that, incoherence and inconsistencies in the EU policies in this region often time originate from these complexities. It also explains to a large extent why the EU revised its neighborhood policies in 2015 and decided to be more flexible and prone to tailor-made policies in its cooperation with its partners in the east and south.

Take alone the South Caucasus in the EU eastern neighborhood. It is a very complex geography in itself with a lot of divergences in policy orientations. In this region, the EU had signed AA/DCFTA (Association Agreement/Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement) with Georgia, CEPA (Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement) with Armenia, and negotiates a new type of agreement with Azerbaijan. Ideally, the EU would prefer to sign AA/DCFTA with all South Caucasian countries. Yet, structural conditions in the region and the regional countries offer different possibilities. It leaves the EU with two options - either to disengage from there or to appropriate its actions according to the local conditions and as well as, prevailing regional order.

Overwhelming focus on the EU. To some experts, the neighborhood is seen as an object of the EU’s policies, not a subject. Due to this, slightly unilateral, incomprehensive, and one-sided data are produced, and findings fail to grasp peculiarities on the ground in the individual neighborhood countries. Many perceive a bigger role for the EU more than a neighborhood country in the successful implementation of, for instance, the normative or transformative agenda of the EU envisioned in EUGS 2016. They do not take into account the world visions, imaginaries of neighboring countries, orientations, and structural preconditions under which they operate. As a result, what fits the EU’s needs and how to achieve this in a neighboring country is the main focus. A solution to the problems in a neighboring country or how a policy advocacy might affect or be perceived by a neighboring country is not a concern. According to this perception, often the EU is not found accountable to the relatively weak neighborhood country and may do whatever it pleases despite resistance.

Discursive implications. A Group of experts anchor their recommendations in the EU’s transformative and normative harbor. From that angle, ‘whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy and whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend’ as famously said by George Orwell in his ‘Animal Farm’. In other words, thanks to this kind of discursive implications, stimulating pledges such as progress, prosperity, liberty, freedom, dignity, and a better future turned out to be synonyms for cooperation with the EU, while alternative development narratives have been associated with unpromising and repulsive meanings. Knowledge/policy production of this type is a utility-maximizing strategy. This strategy serves to construct the EU’s normative identity to regulate the force of interactions on the ground and to create a field of maneuver for the EU.

The term neighborhood is not an impartial or pure geographical category but a political category. It is a territorializing term that aims at creating a ring of well-governed states around Europe. Neighborhood is not a geographical and political reality. The term has a lot of associations, like remaking the regions around Europe, redefining existing hierarchies, reordering power relations, granting authority, or the right to interfere, etc. To put it differently, the term neighborhood defines the geographies where the EU assumes it has responsibility on the one hand and capacity on the other hand to territorialize the flows of the goods, services, labor, capital, entrepreneurship, and knowledge to better position vis-à-vis its competitors.

The same is largely true about the categorization of the neighborhood as eastern and southern. It was an arbitrary decision made by the EU. Thanks to the penetration of these arbitrary divisions informed by political decisions into academia and practical domains, there are plenty of misunderstandings, stereotypes, and wrong generalizations about the neighborhood. Thus, taking the EU’s categorizations as units of analysis without contextualization, and making a statement about them is either methodologically problematic or is participating in the EU’s project of region-building (intentionally or unintentionally).

***

Epilogue. The countries that the EU included in its neighborhood policy are increasingly unstable. They deal with many social, economic, and political problems simultaneously. They are vulnerable, not resilient, and unprotected vis-à-vis foreseen and unforeseen risks as the majority of them are not members of any well-functioning security community or economic blocs and are not going to be any time soon. Yet, it does not necessarily mean that global and regional powers have the comfort of neglecting or ignoring their vital interests when initiating their territorializing projects in these geographies.

It should be noted that any one-sided adjustment policies will definitely have negative consequences not only for these countries but also intervening powers and their people as we live in a globalized world. That is what is being witnessed in Europe and around the different corners of the world nowadays. In the same regard, any successful implementation of the EU’s external policies in neighborhood contingent on again recognition of the interests of these countries and respecting their sovereignty as Biscop says ‘Not only is it far from clear who is to be made resilient against what where there is no more or less benign government but, where countries are only just coming out of war, their first priority is national survival, and their demand is for security guarantees. Would sovereignty and equality not be a better leitmotiv for EU strategy in the neighborhood?’