China’s perception, goals, and foreign policy for Central and Eastern Europe

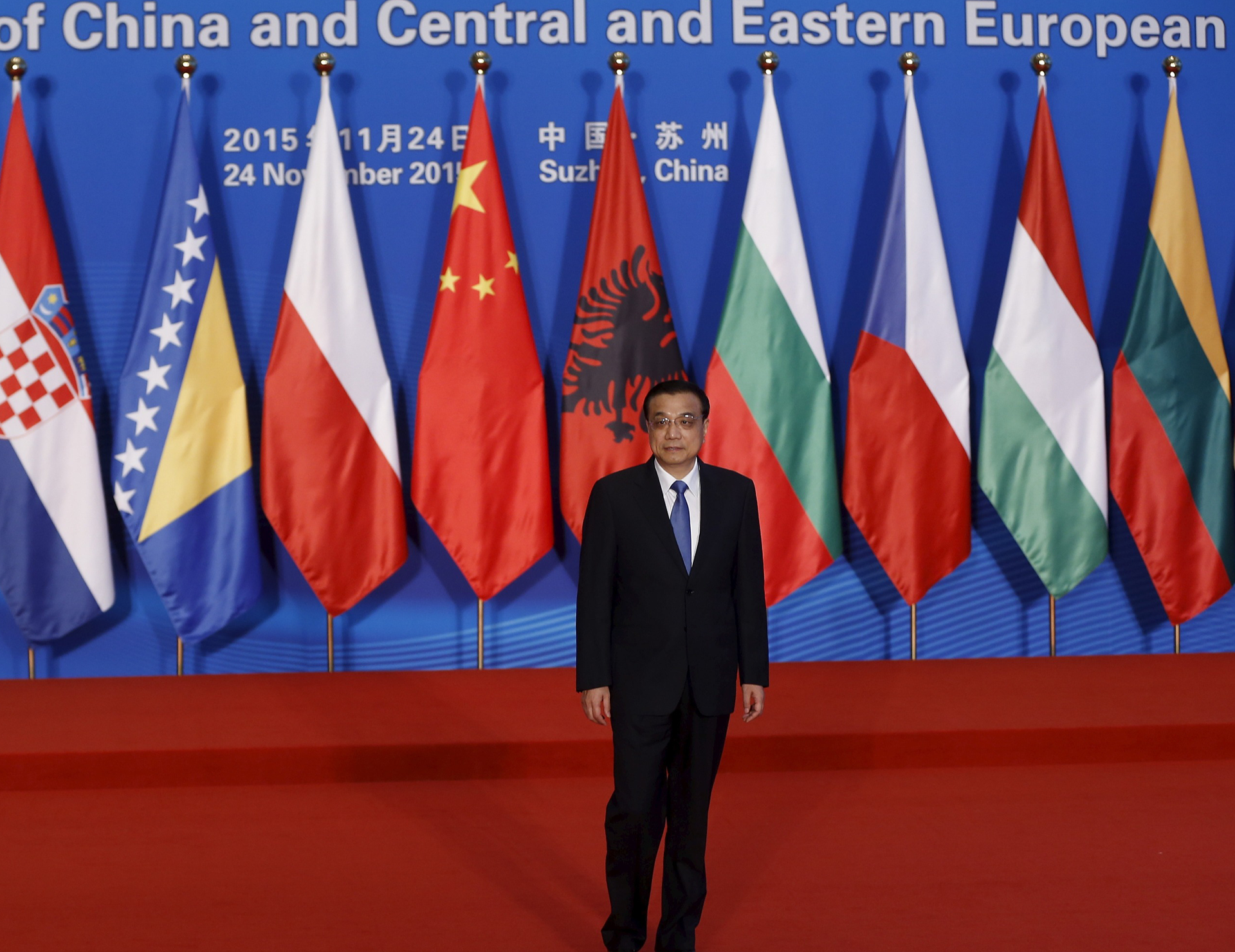

The Central and Eastern European (CEE) region has been a focal point of China’s foreign policy for the past decade, particularly within the framework of the 16+1 (now 14 after Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia’s withdrawal) initiative. Established in 2012 at the summit in Warsaw presided by the then-Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, the platform was initially heralded as a promising collaboration aimed at fostering economic ties between China and CEE countries. The initiative involved 16 countries—later expanded to 17 with Greece—and promised significant economic benefits through trade and infrastructure development. However, a decade later, the initiative finds itself in a state of stagnation, with China’s ambitions in the region increasingly questioned. To understand China’s approach to the CEE region, it is essential to examine how Beijing perceives the region, the goals it pursues, and the role the region plays in its broader foreign policy strategy. These questions reveal a complex and evolving dynamic that underscores both the opportunities and challenges inherent in China-CEE relations.

How does China see the region?

China’s perception of the CEE region is shaped by historical, economic, and geopolitical considerations. Since the inception of the 16+1 initiative, Chinese experts and officials have viewed the region through two primary lenses: historical legacy and economic opportunity.

Beijing often emphasizes its historical ties with the CEE countries, rooted in their shared experiences as socialist states during the Cold War. Many CEE countries established diplomatic relations with China shortly after the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, creating a narrative of a long-standing friendship. Chinese policymakers argue that both China and the CEE countries share a history of colonial subjugation and struggle under the influence of larger powers. This narrative positions China as a partner that understands and empathizes with the region’s challenges, fostering an image of mutual respect and solidarity. However, this historical framing has its limitations. While it may resonate rhetorically, it does not fully account for the region’s integration into Western institutions such as the European Union (EU) and NATO. The transition of CEE countries from socialist regimes to democratic states and market economies has distanced them from the ideological commonalities they once shared with China. For instance, countries like the Czech Republic and Lithuania have actively criticized China’s human rights record, signaling a significant divergence in values.

Economically, the CEE region has been perceived by China as both a potential market and a gateway to Europe. In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, the region demonstrated relative resilience compared to Western Europe, attracting Beijing’s attention. Chinese policymakers viewed CEE countries as prospective partners for trade, infrastructure development, and investment, particularly in bridging the gap between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ EU member states.

Nevertheless, Chinese experts also view the region as economically underdeveloped and dependent on external assistance. CEE countries are often characterized as small and politically fragmented, with limited economic weight within the EU. This perception has influenced China’s approach, treating the region as a collection of secondary players rather than as an integrated or independent bloc. Moreover, the region’s ongoing need for infrastructural development and digital upgrades, such as 5G, has been a focal point for Chinese investments. Notably, Poland and Hungary were targeted as key hubs for Chinese projects, though many of these initiatives failed to materialize.

China’s goals in the CEE region

China’s engagement with the CEE region has been driven by several strategic goals, ranging from economic interests to geopolitical calculations. These goals reflect both Beijing’s immediate priorities and its long-term aspirations.

One of China’s primary objectives in the CEE region has been to secure market access for its goods, services, and investments. The 16+1 initiative was initially designed to promote trade and economic cooperation, with promises of large-scale investments in infrastructure projects. These efforts aligned with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which seeks to create a network of trade routes connecting Asia, Europe, and beyond.

However, these economic ambitions have often fallen short of expectations. Chinese investments in the region have been modest compared to initial promises, and many projects have been delayed or abandoned. For instance, the much-publicized Belgrade-Budapest railway, a flagship project under the BRI, has faced repeated delays due to regulatory hurdles and funding issues. This has led to growing skepticism among CEE countries about China’s commitment to fulfilling its pledges.

From a geopolitical perspective, the CEE region occupies a strategic position in China’s broader European policy. By engaging with CEE countries, Beijing aims to establish a foothold in Europe and potentially influence the EU decision-making. The inclusion of Greece in the 17+1 framework in 2019 was a significant move, reflecting China’s interest in leveraging the region as a gateway to Southern Europe and the Mediterranean.

At the same time, China’s approach to the CEE region has been marked by a lack of consultation and coordination with the EU. This unilateralism has fueled concerns in Brussels about Beijing’s intentions, with critics accusing China of attempting to divide Europe by exploiting economic disparities between CEE and Western European countries. The decision by the Czech Republic to sever Prague’s sister-city ties with Beijing in favour of Taipei further highlighted the growing divide.

Another key goal for China has been to counterbalance Western influence in the region. Chinese experts often characterize CEE countries as dependent on external powers, particularly the United States and Western Europe. This dependence is seen as a barrier to closer China-CEE relations, with Chinese analysts frequently attributing the region’s critical stance towards Beijing to US pressure.

The case of Lithuania exemplifies this dynamic. Lithuania’s decision to deepen ties with Taiwan and withdraw from the 17+1 initiative has been framed by Chinese experts as a result of the US influence. Similar narratives have been applied to other CEE countries that have adopted policies perceived as detrimental to China’s interests. For example, Romania’s cancellation of a nuclear power plant deal with a Chinese company in 2020 underscored the growing wariness of Chinese investments.

The role of CEE in China’s foreign policy

The CEE region plays a secondary but strategically significant role in China’s foreign policy. While Beijing does not view the region as a priority on par with major powers like the US or Western Europe, it sees CEE as an intermediate zone that can serve as a testing ground for its broader geopolitical ambitions.

Chinese analysts often describe the CEE region as a “playing ground” for great powers, drawing parallels to Maoist-era concepts of intermediate zones. This perspective underscores Beijing’s view of the region as a space where external powers, including the US, EU, and Russia, compete for influence. By positioning itself as an alternative partner, China seeks to navigate these dynamics and carve out a role for itself. However, China’s alignment with Russia has complicated its position in the region. Beijing’s tacit support for Russia’s actions in Ukraine and its framing of the conflict as a geopolitical struggle between the US and Russia have alienated many CEE countries. This has reinforced the perception of China as a security threat and undermined its efforts to build trust in the region. Poland, for instance, has been particularly vocal in its criticism of Beijing’s stance on Russia.

China’s foreign policy towards CEE has also relied on leveraging economic tools to achieve its objectives. Investments in infrastructure, such as railways and ports, are designed not only to boost trade but also to enhance China’s strategic presence. However, the limited scale and scope of these investments have diminished their impact, leading to frustration among CEE countries. Moreover, China’s punitive actions against countries like Lithuania highlight its willingness to use economic coercion to achieve political ends. This approach has backfired in many cases, further eroding Beijing’s credibility and soft power in the region.

How does the region align with China’s foreign policy?

The alignment between CEE countries and China’s foreign policy has been tenuous at best. While some countries, such as Hungary and Serbia, have maintained relatively close ties with Beijing, others have grown increasingly critical. This divergence reflects both internal and external factors.

Within the CEE region, disillusionment with China’s unfulfilled promises has been a significant factor. The lack of tangible economic benefits, coupled with concerns about debt dependency and political risks, has led many countries to reassess their engagement with Beijing. This has been particularly evident in the declining participation in 16+1 summits and the growing criticism of China’s human rights record.

Externally, the region’s alignment with the US and EU has created additional obstacles for China. The intensification of US-China strategic rivalry has placed CEE countries in a difficult position, as they seek to balance their economic interests with their security commitments. Similarly, the EU’s increasing scrutiny of Chinese investments and its push for greater transparency have limited Beijing’s room for maneuver.

As the 16+1 initiative enters its second decade, the future of China-CEE relations remains uncertain. To navigate this complex landscape, both sides will need to reassess their strategies and priorities. For China, this means addressing the region’s concerns and adopting a more transparent and consultative approach. For CEE countries, it involves balancing their economic interests with their commitments to democratic values and security partnerships. Ultimately, the evolution of China-CEE relations will serve as a microcosm of the broader challenges and opportunities in China’s engagement with the world.