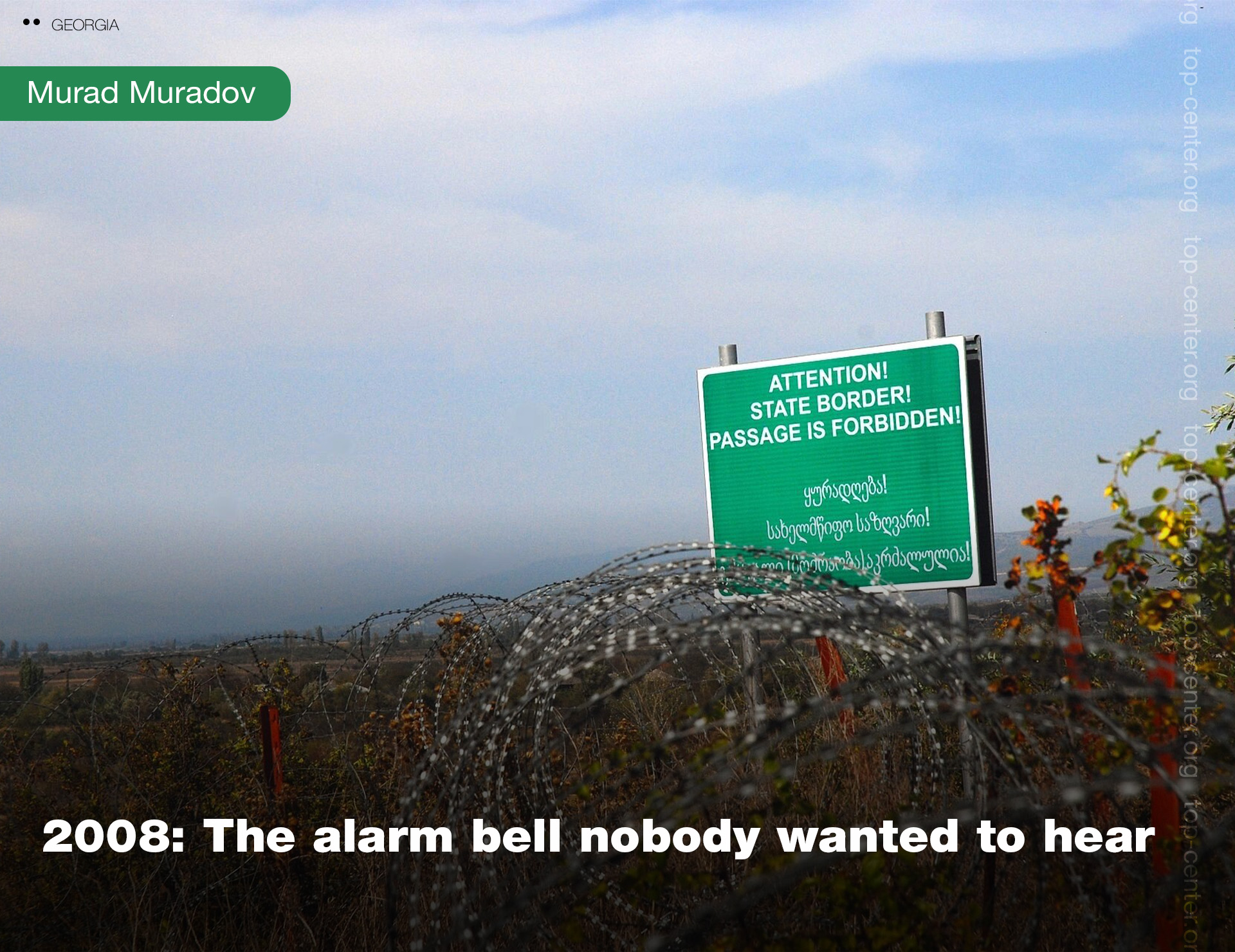

2008: The alarm bell nobody wanted to hear

These days mark the 14th anniversary of the 2008 South Ossetian war. Fourteen years have already passed since the time when the world, assured of the idea of the inviolability of state borders and the impossibility of a war of aggression in Europe, followed the march of Russian tanks through the Georgian territory, threats of execution against the legitimate head of the Georgian state and the Western leaders begging Russia to stop short of the full-fledged occupation of a sovereign country, the member of the Council of Europe willing to become an EU and NATO member one day. Putin did stop, and life continued as usual, while popular attention would very soon shift to the gloomy realities of the financial crisis. In one of his foreign policy moves, the new President Obama declared the “reset” with Moscow, reviving the end-1980s images of responsible cooperation between the two superpowers. In Russia, the reign of President Medvedev, who had initially been cheered in the West as an aspiring young liberal, would end in his surrender to Putin 2.0., the much more hawkish and uncompromising version of himself. He took the popular uprising in Ukraine as the West’s plot against himself, and didn’t hesitate to ignite militant separatism that took tens of thousands of lives and turned Ukraine’s richest region into wasteland. A year later, he moved Russian troops into Syria, giving a new breath to the already-falling Syrian regime.

However, the Western reaction to Putin’s voluntarism remained lukewarm. While decrying Russia’s aggressive and illegal acts and introducing economic sanctions of rather dubious efficiency, most Western states would continue to shut their eyes to the Western companies’ work in the strategic sectors of Russian economy. German and French firms would continue to build strategic infrastructure and enable military industry development in Russia. This half-hearted approach convinced Moscow that the Western countries today are hypocritic as they don’t practice what they preach at all. Putin came to view the EU as a powerless but pretentious figure, who started to define his policy towards the West and Ukraine in the recent years as a confrontation and best possible opportunity to teach them a lesson. As the effects of initial sanctions waned, Russia would only gain from rising commodity prices and global instability.

And in 2022, we have to witness in horror the outrageous war in Ukraine, driven by the mix of Russian imperial nostalgia, disregard for international norms and Putin’s personal idiosyncrasies. And when it is no longer morally tenable not to take radical steps and continue “business as usual” with Russia, it is also very costly- much costlier than it would have been in 2008. While most Western countries tried to benefit from Russian hydrocarbon galore and easy investment, they now find themselves in the situation where a radical rupture means real pain for millions of citizens, while many non-Western countries, who witnessed this half-hearted approach for 14 years, now prefer to make their own policies and don’t haste to join the anti-Russian train. Georgia, which was then spared of occupation and humiliation, is still in an uncertain position and if the real risk of new invasion from the north materializes, this vital geographical link between Europe and Asia may be lost as well. So, it seems that the lessons of 2008 are finally being learned only in 2022. It must be clear now that liberal ideas and globalism do not win by virtue of their merits, that their proponents must be represented by honest and trustworthy leaders, not afraid of taking hard decisions and taking up challenges instead of sacrificing the small and the weak to preserve the illusion of peace and security.