Renewal of democracy: post-election challenges faced by the United Opposition

On the 15th of October 2023, parliamentary elections were held in Poland. What distinguishes these from other free elections before them is the record-breaking turnout of 74.38%. The closest turnout in contemporary parliamentary election history (62.7%) was achieved in 1989, during Poland’s first partially-free elections after the communist rule.

This high turnout can be associated with the rise in civil society activity during the eight-year rule of the Law and Justice (PiS) party, as well as particularly intense, brutal, and personal political campaigns. The first reason is connected to the controversial political decisions undertaken by PiS, which in many cases were perceived by critics and observers as unconstitutional and anti-democratic. Several of these decisions affected Poland’s relationship with its Western allies, and more importantly, with the European Union, which intervened on numerous occasions.

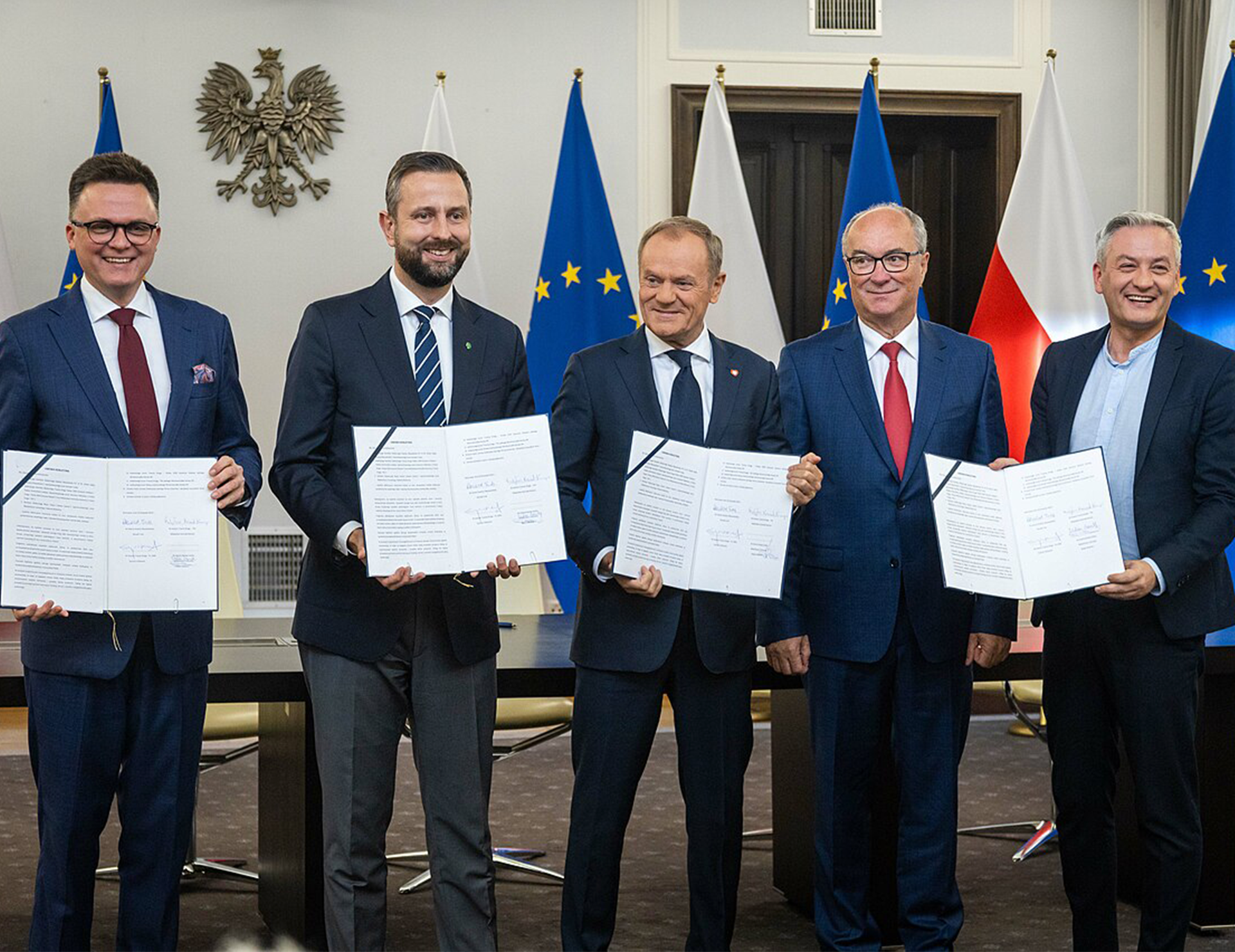

Although Law and Justice won the majority of votes – 35.38%, it does not have enough electoral mandates to form the government. The United Opposition, formed by the Civic Coalition (KO), Third Way (TD), and New Left (NL), has 248 out of 460 mandates, making them the strongest force in the new Sejm, which is the lower chamber of the Parliament. But before the United Opposition can enjoy the privileges and responsibilities of victory, they must first form the government.

Their ability to do so is limited by President Andrzej Duda, informally associated with PiS. Designating the prime minister is a part of his competencies, and the custom has been to choose a candidate from the victorious party. This time, however, the case is unprecedented and needs an extraordinary approach. Historically, even if the winning party did not get enough mandates, it was able to quickly form a coalition, ensuring a smooth transition of power in the upcoming term.

This time however, the President was faced with a tricky choice. He could either choose a candidate according to the expectations of his former party – which would be the former Prime Minister from PiS, Mateusz Morawiecki – or defy these expectations and designate the candidate of the United Opposition, the man who became the main target of Law and Justice’s electoral campaign – Donald Tusk.

As his deadline approached, President Duda during his Presidential Address, quite unsurprisingly, ended up choosing Morawiecki. This, of course, led to a delay in transitioning smoothly into the new government. After the elections, the President had 30 days to convene the first session of the parliament. On the 13th of November that first session was held, with former Prime Minister Morawiecki handing in the resignation of his government. From that date, Mateusz Morawiecki has two weeks to present a proposition of the new government along with a motion of confidence. As it is clear from the distribution of mandates, the most likely outcome is that PiS will not achieve the absolute majority needed to obtain the vote of confidence, and therefore the process will have to be repeated in the parliament, this time without the President’s interference.

During that first session of the Sejm, Szymon Hołownia – one of the leaders of the Third Way and the United Coalition – was chosen for the position of the Marshal of the Sejm by the absolute majority. His opponent was Elżbieta Witek from PiS, former Marshal of Sejm. Witek has been accused by the United Opposition’s politicians of violating the principles of parliamentarism and the law in her previous term. She is infamously known for controversial re-assumptions of votes and limiting the ability of opposition MPs to speak.

Particularly interesting during the first session was also the vote for Deputy Marshals of the Sejm. It is customary for every party in the Sejm to have a representative among the Deputy Marshals. Elżbieta Witek was the only candidate to not receive enough votes, leaving Law and Justice the only party without representation, at least until a new candidate is proposed.

But at the end of November, when the new government is hopefully finally formed, it will stand before the responsibility to fulfill the promises made to its electorate. Most of these promises have been about “cleaning up the mess” left behind by Law and Justice. This refers to the aforementioned decisions deemed by many as unconstitutional and anti-human rights, but also to the issue of the country’s 1.24 billion PLN debt.

The first challenge is transforming the state of the judiciary. Since coming into power in 2015, Law and Justice initiated significant changes to Poland's judiciary system, drawing both national and international scrutiny. The party's reforms, including the lowering of retirement age for judges, restructuring of the Supreme Court, and the introduction of disciplinary measures against judges critical of government policies, raised concerns about the independence of the judiciary. Critics argued that these changes undermined the separation of powers, eroding the checks and balances vital for a democratic society. The European Union, too, expressed deep apprehension, leading to several clashes over the rule of law. These reforms not only polarized the nation but also strained Poland's relationship with its European counterparts, underscoring the challenges faced by the opposition in their bid to restore the integrity of the country's judicial system. First of all, it is necessary to implement the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights against Poland. Apart from obvious steps like the aforementioned one, further action should be taken in accordance with recommendations from prominent NGOs such as Batory Foundation’s report titled How to restore rule of law? and Iustitia Association of Polish Judges’ draft bill on the restoration of the rule of law. Sylwia Gregorczyk-Abram, a lawyer from The Free Courts initiative, estimates that this transformation should be mostly completed as soon as within a year of the new parliament’s term.

When the rule of law is restored, as many as 14 judgments of the Constitutional Tribunal should be deemed null and void. One of them is a verdict imposing even stricter regulations regarding the right to abortion. Since 2015, Poland's Law and Justice party has made several attempts to tighten the country's abortion laws. In 2016, a proposed bill aimed to ban abortion in all cases except when the mother's life was at risk, sparking massive protests and a women's strike. Although this proposal was rejected, in 2020, the Constitutional Tribunal, influenced by PiS, declared abortions in cases of severe fetal abnormalities unconstitutional. This ruling effectively restricted abortion rights, leading to international criticism, and one of the biggest protests in contemporary Poland, estimating one hundred thousand citizens gathering in the capital of Warsaw. Even in the case of annulment of the 2020 judgement, the case of the right to abortion remains controversial among the United Opposition’s politicians. The leaders of the Third Way, the second biggest opposition party, have openly expressed their hesitation about liberalization of abortion laws. They have openly opposed the inclusion of the issue of legalizing abortion in the coalition agreement, and suggested holding a referendum on the matter.

The third challenge is the LGBT+ rights. Law and Justice has been conducting a hateful campaign against sexual minorities since the beginning of their rule in 2015, with intensification in 2019, connected to the introduction of resolutions known as “LGBT-free zones”, adopted by local government units with a majority of PiS members. This provoked reactions from the Polish Ombudsman, but also from various foreign politicians, including Ursula von der Leyen and other high-level representatives from the European Union. The EU even adopted several resolutions directly referencing the new Polish laws. One of the pillars of the United Opposition’s campaign was the promise of equality and respect for everybody, regardless of their gender identity and sexual orientation. The most pro-LGBT party in the coalition, New Left, has received the least number of mandates, setting the expectations of the queer community low. In the coalition agreement, LGBT+ community was mentioned only in the case of protection from hate speech and discrimination. For more radical solutions, like the adoption of civil partnerships and increased quality of sexual education at public schools, the LGBT+ community will have to wait.

In this pivotal moment, the Opposition faces a series of intricate challenges. Striking the right balance between progressivism and pragmatism should be their leading objective. As they move forward, their ability to harmonize diverse voices and ideologies will be crucial. The eyes of each citizen are on them, watching their moves with anxiety, distrust, and in many cases – hope. The last eight years have awoken a sense of responsibility, determination and passion in Polish society. The future cannot be predicted, but one thing is certain – the young generation, with their turnout highest in comparison to previous elections, will be the one who makes sure that politicians are held accountable for their promises.